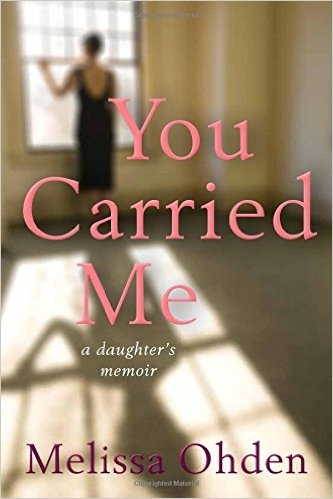

A Book Review: "You Carried Me" by Melissa Ohden

The well-documented and dramatic details of Melissa Ohden’s survival stand on their own as an important memoir, and are made more valuable by an invitation to readers to consider their own experiences of suffering. Chapter eleven of You Carried Me: A Daughter’s Memoir, opens with an epigraph by author Zora Neale Huston: “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story within you.” Ohden’s emphasis on welcoming the untold stories of others is her greatest strength, and what makes her book a life-changing parable for anyone willing to listen.

Throughout her life, the author navigates a tangle of untold and unwelcome story. Where she imagines as a child that her birth mother gave her up for adoption in a loving act, she discovers, instead, she’d been left for dead after a failed saline infusion abortion. She spends her teenage years alternately escaping and grieving that harsh truth, and hopes for a regained sense of self in academic pursuit. As the first person in her adoptive family to attend university, she imagines a confidence gained with collegial acceptance. She discovers, instead, a chilled response from her peers and outright rejection from her professors. She painfully concludes, “In the midst of conversations about every kind of abuse, abandonment, and human heartache, I learned quickly that my story was one that could not be heard, and therefore must not be told.”

And this is only the beginning.

From here, Ohden begins the arduous and lonely process of searching for the truth about her biological family. Where a different storyteller might connect together the details of this search like a movie montage - discovery to dreadful discovery - Ohden insteads lays out a chronological journal covering the decades of her search. In reality it takes years (well beyond the scope of a dramatized movie scene) for her to not only find, but absorb, each new detail punctuating her otherwise ordinary Midwestern life.

Perhaps most importantly, Ohden creates a gracious space to not only give account for the tenacious uncovering of her tragic and miraculous birth story, but to also frame her story within an offer of hospitality. Page after page, she invites us to see beyond the surface of her daily life (childhood financial insecurity, pursuit of academic degrees, vocation, marriage, children, faith, and social activism) into the complexity of her internal turmoil and, then, acceptance of the real story of her origins - the good, the bad and the truly devastating. It’s in this methodical untangling, I find the unique gift of hospitality she offers to discerning readers. She welcomes us to fully engage with our own struggles at every level - body, soul and spirit.

As a newborn, in order to survive a premature birth induced by days of ingesting poisonous saline, Ohden fights for survival at a cellular, completely physical level. As an adolescent, Ohden fights at a more emotive level - absorbing the shame of the knowledge her existence was completely unwanted. She responds to the depth of that shame in some completely natural ways that further damage her sense of belonging within her adoptive family and among her school and church communities. Still, she persists toward a deeper truth about herself and the Being who formed her in the young, unwed womb of the woman who - for reasons Melissa wouldn’t know for decades - did not want her. As a young adult, Ohden presses into her story with her mind - trying to grasp the realities of human behavior and development through her studies in psychology and social work. As she encounters the stories of others, she seeks to understand better her own.

And then, as a thirty-something wife and mom, we walk with Ohden through a more complete spiritual surrender to the mystery of faith, doubt, suffering and forgiveness. Maybe this is is the progression of healthy human development - a response of body, soul and spirit to both the banal and truly tragic events of our lives, but how many of us willingly engage our total selves with those realities? I find that sort of whole-heartedness to be a rare response, and one Melissa Ohden models beautifully for all of us. Her courage to share her story after repeated rejection and full-scale shunning invites us, the reader, to our own moment of choice.

We, the readers, can choose to welcome the totality of Melissa’s story or we can, like her collegial and professional peers, choose to look away. Even further, we can choose to honor the author’s courage by embracing the complexities her story represents, or dishonor it by cherry-picking the parts of her life that further our own social, political or religious agendas.

Ohden’s story is inconvenient to everyone with deeply-held convictions on reproductive rights, no matter what their political posture. For those who’d choose to dehumanize her preborn self, there’s the reality of her will to survive the attempt to end her existence. For those who who’d choose to dehumanize men and women faced with unplanned pregnancies, there’s Ohden’s insistence on mercy, forgiveness, insight and acceptance of her own biological parents. For the reader who would deny the equal dignity of womanhood, Ohden persists in championing women’s rights. For those who’d argue no child should have to suffer physical limitations, she shares the experience of welcoming the complex health problems of her youngest daughter while growing in empathy for those “tempted to choose abortion to avoid this fate.” To those who would deny the role of grief and suffering within faith, Melissa tells about the miscarriage of her second child and professes solidarity with “women everywhere who have lost a child in any way. Whether our child died through illness or accident, abortion or miscarriage, we share an unspoken bond of sorrow.”

The author’s perseverance to not only know the truth, but to know it within the bounds of love make her life story more complex than mere survival. Like the unnamed and unclaimed two-pound newborn fighting to live against the odds, Melissa invites us all to a greater miracle: forgiveness and reconciliation. She shows us that this is what’s required for a life that flourishes.

On a personal level, I found Melissa Ohden’s memoir to be most inconvenient to my disenchantment with pro-life activism. I am older than the author by only a few years, both of us children of the 1970’s and 80’s. The historic Roe v. Wade decision framed almost my entire view of both the religious and political worlds in which I grew up. As a child raised in more conservative church communities than Ohden, it was completely normal to find me on any given day of my high school and young adult years protesting the politics of reproductive rights, picketing abortion clinics in my hometown and across the northeastern U.S., petitioning state congressional leaders and writing opinion articles for religious newspapers. When I was 17, I watched through a fence line while police officers arrested my father for trespassing at a local abortion clinic during a nonviolent protest. On my eighteenth birthday, I visited him in the county jail where he served a one-month sentence for that protest.

I’ve never stopped carrying a deeply-formed conviction that human life begins at conception and that any attempt to intentionally end that life is a human tragedy by both biblical precept and basic civic moral codes. I have, however, spent most of my adulthood distancing myself from the sort of activism that framed my youth. I became severely disillusioned by the community of people who identified as pro-life on one issue only, while fiercely opposing matters of life on so many others. In my secluded Protestant upbringing I knew little of the long history of Christian teaching on a consistent life ethic which spanned the range of life-threatening issues I intrinsically questioned: war, abortion, poverty, racism, the death penalty, gun control and euthanasia.

Among those whose actions shattered my idealism was one of the key leaders of a nationally-known pro-life organization who lived in my hometown. He sent his kids to the same high school I graduated from, and led protests and prayer gatherings alongside area clergy like my father. I can trace my decision to separate myself from this particular brand of activism back to two defining moments: the mid-90’s abortion clinic bombings and news that the pro-life leader we’d followed had abandoned his wife and children in order to marry his former church assistant. If this is what it meant to be “pro-life”, I wanted to get as far away from the label as possible.

Melissa Ohden’s persistence to live out her heartbreaking story with the courage of hope, healing, and forgiveness invites me to reexamine the integrity of my response to disillusionment. If she can be joyfully reconciled to the woman who (against her own will) left her for dead, then I most certainly can be reconciled to honorable communities of people who speak up for the defenseless. She didn’t choose to be pro-life as an idealistic posture, her very existence speaks for itself the sacredness of human life.

For the reader who longs, like me, to acknowledge every human being as image bearers of God, Melissa Ohden’s story should not be overlooked or oversimplified. The image of God was fully developed within the mother who carried her. She, like us, could do nothing to manufacture that dignity. It’s freely given to each of us, and we are made to not just live but flourish with that recognition.

When it came Ohden’s time to accept or reject the dignity freely offered, she chose to flourish within the paradox of God-given grace that does not replace suffering but, instead, carries us through it. This choice is what makes her story especially important to those of us wanting to love humans well. It is a grace that offers to carry us all.

Go to my Book Reviews page to see reviews from 2016 and previous years.

Here's my Goodreads page. Let's be friends!