A Few More Words On the Hole In Wendell Berry's Gospel

I've received some of the greatest gifts of my writing life since publishing this essay in Plough Quarterly’s winter issue last month. I knew I was taking a risk by critiquing the absoluteness of ideals author Wendell Berry, beloved by me and countless others, promotes in his work. I expected lots of people to disagree. I guessed right. What I wasn’t sure how to calculate is who might actually agree with what I had to say. I took some comfort in knowing that, at the very least, the journal's editors thought there was some value in what I had to say. With this sort of low expectation, you might be able to imagine my surprise when Rod Dreher wrote an overwhelmingly gracious and eloquent response at The American Conservative. I read each paragraph carefully, expecting the shoe of disapproval to drop at some point. It never did.

I also did not expect the level of grace and thougtfulness from those who wrote objections to my essay. This is not the first time Jeffrey Bilbro has offered me a genial counterargument to my thoughts on Wendell Berry’s fiction. His response (published at Front Porch Republic) to the Plough article includes a friendly admonition to me for not heeding his earlier advice to become more familiar with the range of characters and conflicts within Berry’s fictional Port William. He’s not wrong. Although I continued to read a copious amount of Berry’s writing, when Plough contacted me about expanding the essay from its earlier version published at Art House America, I did not take Bilbro’s recommendation to update literary references much beyond Hannah Coulter and Jayber Crow.

Instead, I pressed further into my own story and into the teaching of historical Church leaders like Dietrich Bonhoeffer. I spent more time looking into Wendell Berry’s real-life experiences growing up in Kentucky, a state fighting to keep its agrarian livelihood. In the context of our national election, I'd read J.D. Vance and found myself intrigued by the parallels and differences between his experience of Appalachian culture and Berry’s. In hindsight, I realize I could just as easily have referenced Rod Dreher’s beautiful book describing the care his hometown offered his terminally-ill sister, Ruthie. I first read The Little Way of Ruthie Leming in 2013, and noted then that Dreher’s account was a pleasant contrast to my concerns with Berry’s smalltown depictions.

I think one of the better outcomes for this conversation is for us all to accept Bilbro's challenge to not overlook the "seamier side of Port William's history". As he and Jake Meador (the author of this critique) have indicated, I am not a Berry scholar, merely a literary fan (reading, up to this point, about half of his fiction and poetry, and a third of his nonfiction). In addition to my work as a freelance writer and priest's wife, I've spent a lot of time in ministry caring for those who have been relationally, emotionally and sexually abused. Without placing too heavy a weight on the conversation, I'll admit that a certain amount of the frustration I experience with the rural folk in Port William cannot be separated from my own stories of sexual abuse within a rural community. It'd be fair for anyone critiquing my essay to wonder if I may be projecting my own real-life story onto the Port William membership. At the same time, I'd argue that this is one of the reasons any of us read. We are searching for stories to help us know others and ourselves better. And, for this reason if no other, I am forever grateful to Mr. Berry for helping me to think, maybe especially, when I feel frustrated with the characters he crafts.

This is what I found most rewarding about Dreher’s feedback to my essay. While I enjoyed the fact that he used words like “provocative” and “truth-telling”, tears came to my eyes when I read sentences like this:

“Until reading Murphy’s essay, I hadn’t realized how much Wendell Berry reminds me of my dad…”

and in his follow-up post:

"Murphy’s essay resonated with me, in large part because I try to be vigilant against my own tendencies to romanticize the past."

These words are the highest compliments anyone could ever give me. It's this sort of reflection I find conspicuously absent in the rebuttals from Bilbro and others who seem to engage the conversation at the literary level alone.

As I’ve been given the gift to reconsider my essay, I’ve been able to gain clarity what I’m hoping to say in response to those who wish to follow his ideals. While it’s true that Wendell Berry warns readers against trying to “find a message” in his fiction, it’s also true that many people do, indeed, form life values inspired by his skillfully crafted descriptions of the beauty of agrarian life. Wendell Berry offers a credible viewpoint that counters the dominant cultural obsession with an economy built on industrialism and mobility-at-all-costs. Unfortunately, there is little pushback to this cultural stance from within our evangelical subcultures, making Mr. Berry's voice invaluable. I say, wholeheartedly, thank God for Christians who read and emulate Wendell Berry's life and work, and for those within the Christian community who read Berry's work spiritually. I would include myself - to some extent - as one of them.

My response to the Port William membership is not a critique on Berry’s ability to write excellent stories (which he unequivocally does), but to say that there’s a noticeable dissonance between the Port William membership and a community of people wholly-formed theologically. In particular, I’m proposing that Berry often writes characters that resist the sort of full transformation that comes only by way of repentance. In my essay, I highlight Wendell Berry and J.D. Vance’s grandfathers as examples of this kind of repentance. I share the story of my grandmother’s difficult life as an example of the sort of redemption we can find, even within a rural heritage that has not yet embraced repentance. (A side note: Resistance to acts of repentance is not a problem unique to rural communities, but since rural communities are considerably declining, the temptation to gloss over dysfunction increases.)

I’m happy to own any sloppiness on my part that makes it difficult for a reader to see these gospel themes of repentance and redemption as primary for me. In this regard, I am especially grateful to pastor and author Charles Moore for his feedback:

“This is one of the best essays I’ve read in a long time. It’s wonderfully written, gracious, but also hits the bulls-eye when it comes to Berry’s uncritical, romantic idealism. Murphy is spot on in her assessment of Berry. I simply couldn’t agree with her more (even though I like Berry a lot!). She lifts the lid off of Berry’s truncated soteriology....”

Or, to put it as succinctly as one editor: “it’s Berry’s gospel that’s up for debate, not his literary brilliance!”

To those among my Christian friends and colleagues who hold Mr. Berry and his writing up as a model for cultivating good, true and beautiful economies within the world, I’m encouraging us to practice discernment. Ideals are inspiring, but they are not sustaining. When we limit Mr. Berry’s words to ideals, we limit the greater, everlasting function of a gospel-shaped economy.

It’s not that I have no literary agenda for my essay. If I’m being completely transparent, I would love a few Port William’s sequels telling next-generation stories of Hannah Coulter’s children and grandchildren. Within those stories, perhaps Mr. Berry could describe how it might look for them (my generation) to practice resurrection now? In the meantime, I listen to Rod Dreher’s story of life both within and beyond the “borders of West Feliciana Parish”, read my Grandmother’s diary of growing up abandoned and rescued in upstate New York, and keep track of every story I can find describing generational reconciliation.

I am so grateful to everyone who's taken the time to read my essay and offer feedback. I'm including in that gratitude the literary scholars, like Jeff Bilbro (and my friend Dr. Janet Goodrich, the person who introduced me to Wendell Berry years ago), who help us to plumb the depths of generations of Port Williams’ characters. In the meantime, I plan to keep reading Wendell Berry’s splendid words in every genre, and hope to live into the most striking Gospel-call the author gives us - to practice resurrection here and now.

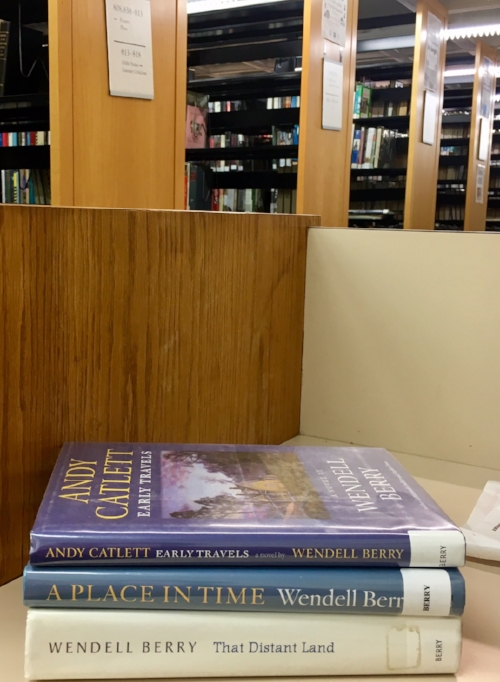

This week I went back to Wendell Berry school.